Georgina Barney is studying for a practice-led PhD at Gray's School of Art, 'Curating the Farm' funded by AHRC (until 2012).

Thursday 24 June 2010

Hello: Georgina Barney

Monday 14 June 2010

Just a short introduction before i go off to explore some badminton spaces with Steve Poole. (I need to make a post otherwise i'll get into trouble.)

I'm an architect, but have spent my career avoiding architecture and being drawn instead to more peripheral, less 'architectural' spatial and critical practices.

More blurb to follow!

Tuesday 8 June 2010

Introduction - Richard Healy

OUTPOST is pleased to present ‘Strategies for Building’, a solo exhibition of new work by London-based artist, Richard Healy.

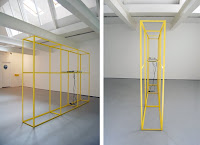

Healy presents us with a series of highly rendered, graphic objects. Four, canary yellow frames support partially rendered pencil drawings depicting prototypes of modernist interiors. Seemingly bleak, the drawings appear as unfinished designs or blueprints. A crisp aluminium shelving system of the same colour houses a projector. The film, anchored through a backdrop of a static horizon, shows a morphing digital landscape of abstract geometry, oscillating between pure abstract form and seemingly recognisable architectural spaces.

'Strategies for Building' continues Healy's exploration of the exhaustion of form, particularly the notion of Minimalism’s search for new possibilities for the object, a search shared and continued by minimal design. Embodied through simulations of architecture and design, Healy’s work explores notions of proposed outcomes, setting his search against the background of ‘future think-tanks’ and ‘invisible committees’.

Addressing the political implications of interior design, the exhibition focuses on a highly regarded and influential colour group. Choosing to remain anonymous this respected group of colour analysts meet twice a year to discuss and forecast colours for various economic outputs based on current observations. Through discussion, a democratic decision is made upon a palette of colours that will be placed into production for use in the next two to three years. Their British palette is then sent, with a representative, to an international colour group workshop, which will form the basis for an international set of colours to be used by multinational organisations. Made up of 23 members, the British group has guided the economic use of colour for over forty years. For the exhibition they have chosen a single colour, which is used throughout as a ‘support structure’ that upholds or contains the artworks.

Healy displays a dichotomy through making simultaneous references to both recognised, existing design histories as well as unrealised ones. His drawings and films imply a time that exists somewhere between or outside the past, the present and the future, where minimalism, an exhausted, historic movement, rubs shoulders with a digital landscape purveying an unrealised environment, a future space. Putting to question the pragmatics of design and its potential to function within an art context, Healy eloquently incites a conceptual playoff between disparate languages and values.

Samuel Jeffery: You have spoken about the framing devices in the show as ‘Secondary Structures’ although they play a critical role within the conceptual underpinning of the work. How did these ‘Secondary Structures’ come to play a primary role?

Richard Healy: Yes their role is critical but equally pragmatic. It is interesting that as I have been discussing these objects I have called them ‘secondary structures’ but also ‘support structures’, in any event they have always seemed dissimilar to the drawings or film. All apart from the aluminium structure, which in its making became increasingly rarefied to the extent that it warranted a title. Interestingly I called it ‘Divider’, so how much can a designed object escape it function? I am not sure, in any case the system of support in the show isn’t universal and that really interests me, especially as they are all a single colour. Monochrome was such a modernist obsession with order, so it’s interesting that the yellow supports are, in fact, unequal to one another.

SJ: The works in the show are pregnant with implied practical and design functions. Even the film, which is potentially the most ambiguous of the works, seemingly manages to retain the quality of a prototype, a draft or maybe even something like an architectural mood board. Is it important that all of the artworks maintain a functional implication, that they seem that they could go on to live different lives outside of the gallery?

RH: It is important that they maintain their elements of function, however I always see these functions through the prism of the gallery space in order to highlight and question their value. The idea of them going into the ‘real world’ to follow their functions is obviously implied, however the reality of that occurring seems less appealing to me.

SJ: You have made a decision to place the printouts of the press release and this interview inside the gallery on a purpose made shelf. These are usually placed in the foyer in racks but between us we have decided to change this system. This way the shelf is almost in the real world and seems to be fulfilling a function that we know was once in the ‘real world’. How would you justify that?

RH: Yes it is fulfilling its function, however I would argue that the gallery is not the ‘real world’ but a ‘pseudo-world’. The distinction between the gallery space and the other areas of OUTPOST like the office, foyer and kitchen are apparent. Choosing to place my works, like the shelf, into those spaces would hinder what that object has been made to do. In that situation I would just be making a shelf for OUTPOST. The fabricated, clean space of this gallery offered the opportunity to question its position and the value of its fellow objects, simply because there is less to interrupt these relationships. I would like to point out that gallery can exist in real spaces, galleries can be in peoples living rooms, if that was the case here my approach would have been very different.

SJ: There appear to be worlds illustrated within the drawings and within the film. These are definitely un-real and fabricated worlds but this is a significantly different kind of thing. In what way is it important for these two types of pseudo-space to come together?

RH: I think it is about control, the opportunity to edit a space. The way in which I have been talking about space as real or unreal is problematic I think. What the white-cube gallery offers is control for the artist, less compromise than in the world outside, hence feeling unreal. The drawings and film are a double of this relationship. The way in how I construct space offers meaning to me, where a chair goes in relation to another object etc. Working in OUTPOST has mirrored this mode of using interior space to construct meaning.

SJ: Looking at the work I have become occupied with a notion of time or, more importantly, a lack or uncertainty of a sense of time. Could you talk about that?

Richard Healy lives and works in London. He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008. Recent exhibitions include ‘Bloomberg New Contemporaries’ at A-Foundation, London (2009), ‘So Much More’ at Meetfactory, Prague (2009), ‘Entry Points’ at Subvision, Hamburg (2009), ‘No Bees, No Blueberries’ (as part of i-cabin) at Harris Lieberman, New York (2009) and ‘Earth not a Globe’ at Rokeby, London (2009)